|

| Straight-from-the-barrel wine for a euro a liter |

About the hardcore runner, my favorite running writer Rachel Toor

says: "He will not, in fact, admit how much of his time training takes up, afraid he will be seen as less serious about the other things he takes seriously." On this blog I've talked about

how I try to conceal from academic colleagues the full measure of my devotion to this hobby of mine. Really, I want colleagues to think that all I do is read and write, that I work all the time and will work harder if challenged to do so. In my professional mind, a hobby is something to conceal, for after all, it has nothing to do with work, and you should make those you work with think you work all the time.

Because professions and institutions promote those who seem to embody the most perfect distillation of their values, I have to appear to others to be the perfect academic, and perfect academics have abivalent and awkward relationships to their bodies. They exercise, but only as part of a fuller productive persona. To me and to many other runners, I think, racing and training have nothing do with work--they're leisure in full, akin to softball or a bowling league. This is compartmentalizing: we don't run to be better at other things, we run to be better runners, or just to be happy. Because it's a hobby. And it's only a hobby. It's discontinuous with work. It's not the substance of our lives, but it's a happy addition.

Over the last few months I've noticed a series of articles that suggests the connotations of endurance sports are changing: no long simple leisure pursuits, endurance sports are seen now as an extension of the work persona, a way to display the traits of tenacity and conscientiousness that make one a successful member of the information economy. Talking about your training, then, no longer means you spend too much time not working--it means you're embodying and perfecting a contemporary work ethos from which leisure and truly personal time have been eliminated. It is true that this amounts to a holistic life, but in this case holism is oppressive.

Maybe you saw David Brooks'

New Yorker article on the so-called Composure Class. Brooks is hit-or-miss and this isn't a post about his reliability as a pop-sociologist, but in the opening paragraphs endurance sports figure prominently as a characterization device of his new representative man:

"He’s just back from China and stopping by for a corporate board meeting on his way to a five-hundred-mile bike-a-thon to support the fight against lactose intolerance. He is asexually handsome, with a little less body fat than Michelangelo’s David...For some reason, today’s high-status men do a lot of running and biking and so only really work on the muscles in the lower half of their bodies."

|

| Left at the Grand Canal--then a mile to the finish line! |

The thing to note here is the association of high status with running and biking, which we see echoed in a

NYT article from October on 40-something triathletes. (That the article appears in the style section and not the sports section says something, not sure what though.) It profiles "a generation of athletic, type-A men who are entering middle age and trying to hold on to their youth through triathlons," notes a 51% growth in the sport since 2007, and focuses on the growing market for bikes, shoes, and other gear among the "alpha consumer" triathletes with an average income of $175,000. Last week, the

WSJ ran a story about the plight of the "exercise widow," whose marriage suffers because his or her spouse takes up endurance sports in earnest. It profiled New Jersey couple Caren and Jordan Waxman. Jordan's a 46-year-old banker who began doing triathlons, and now their marriage is suffering.

Jordan's defense of himself encapsulates the new connotations of endurance sports and what appears, by these accounts, to be their new association with status: "In his view, his athletic ambition shouldn't have surprised his wife. It arose from the same qualities that drove him to obtain two law degrees, an MBA and his position at Merrill Lynch." Great job Jordan! I hope that when he's divorced, if he has time to date, women will at least appreciate his abs. In any case, what strikes me here is the easy equation of endurance sports with ambition. A rationalization probably, but to me, it suggests a guy totally consumed with work, who lets a work mentality cannibalize every aspect of life.

The marital problems of the Waxmans aside, the ambition mentality surrounding endurance sports confers prestige based on distance, slighting high performance in the shorter events that, let's be honest, demand more athletic skill. The marathon begins a continuum that moves through the half-Iron Man to the Iron Man even to climbing Everest, homogenizing each as an accomplishment of determination and time management, as if athleticism were somehow beside the point. It's not often noted because of our cultural fetishization of the marathon, but in many ways the 5k is the harder race. In a marathon, you hurt for a while, but not for the whole race. In a 5k, you hurt from the gun and start to finish it's agony. In the marathon, the pain comes gradually; in the 5k, it comes suddenly and stays. But the people who run sub-16 5ks never get the same Monday morning credit as, say, the office Jared Fogle who carries his chafed armpits and bleeding nipples across the finish line of a marathon in over five hours.

|

| In the garden of the Guggenheim palazzo |

But I digress. If what we're witnessing is the rise of the endurance athlete and the decline of the runner, it's because of a cultural change that has followed in the wake of what economic transformation has come to demand of information age workers like Waxman the banker: devotion, singlemindedness, indefatigability. Of course, the endurance athlete and the runner are not defined by the kinds of sports they do, but by their attitudes toward them. Plenty of people do tri's without fitting the Type-A stereotype described by the Times, while I have encountered participants in footraces whose capacity for self-adulation far exceeds their lactate threshold or VO2 max.

Perhaps a figure for Brooks' composure class, if we accept the notion, the endurance athlete is characterized by intensity, by continuity between work and play. In contrast, the runner is (or was) a figure of leisure, a hobbyist. Typifying the runner would be

Doug Kurtis, now in his late 50s or early 60s and a fixture on the Detroit running scene. With a personal best marathon time of 2:13, Kurtis ran 76 marathons under 2:20, all while holding down a job as a manager at GM (before, following his running prime, he became director of the Detroit marathon). Kurtis ran twice a day for about an hour, once at lunch and once after work. Running never filled Kurtis' whole day but then again, neither did his 40-hour-a-week job. (There's a great profile of him in an 80s Runner's World that I cannot seem to find on the Internet.)

I find the question of how people view endurance sports to be endelessly fascinating, so chime in with what you think. Is there really a change in the connotations of tri's and marathoning, or is this just a case of a few journalists spotting the same faux-trend? Also, notably absent from the trend stories I've seen is any discussion of women, who are the

real story of the running boom of the past few years. In 2000, there were 299,000 marathon finishers, 37.5% of whom were women; in 2009, women comprised 40.4% of the 468,000 who finished a 'thon. So there's a huge increase in participation overall, and more and more of that increase is made up by women.

The moral of the story is, be suspicious of an integrated, holistic life because it's the same mentality that won't let you get away from your work. There's something to be gained by living life in fragments and having a separate persona (an authentically integrated spiritual self is another thing altogether) for each one. It's not schizoid; it's the only way to stay sane. You can't always keep your mind out of your runs, that is, you can't always block everything out, but after a while a run will have a tonic effect that makes you at least feel a little less stressed.

My wife and I did 18 together today! It was great--she was always in great shape but her fitness is really increasing these days. She had no trouble on the run and finished the last mile under the average pace for the whole things. Well done!!

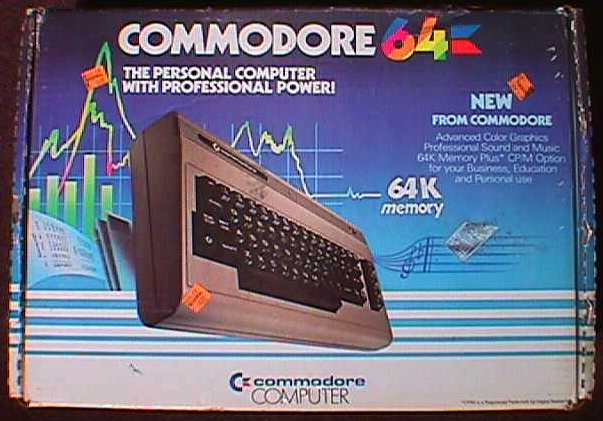

My six-year-old (six in people years, that is) computer's dying--I spent much of the day rebooting as I worked on my dissertation chapter. [Hence this post is a day late.] Next computer purchase will be a PC desktop. More computer power than a laptop and much less pricey.

My six-year-old (six in people years, that is) computer's dying--I spent much of the day rebooting as I worked on my dissertation chapter. [Hence this post is a day late.] Next computer purchase will be a PC desktop. More computer power than a laptop and much less pricey.